In this in-depth guide, we’ll explore the dragon boat paddle technique from multiple angles. We’ll break down the why, what, and how of effective paddling, compare it to other water sports techniques, and address common FAQs. Drawing from established practices outlined by organizations like the International Dragon Boat Federation (IDBF), which governs the sport worldwide, this article aims to provide actionable insights backed by data. For instance, IDBF studies show that proper technique can improve boat speed by up to 15-20% in competitive races, emphasizing the importance of synchronization and biomechanics.

Dragon boat racing is an ancient sport that combines teamwork, power, and precision, originating from China over 2,000 years ago. Today, it’s a global phenomenon, with events like the World Dragon Boat Racing Championships drawing thousands of participants. At the heart of this sport lies the dragon boat paddle technique—a skill that can make the difference between gliding through the water efficiently and struggling against resistance. Whether you’re a beginner looking to join a team or an experienced paddler refining your form, understanding the intricacies of dragon boat paddle technique is essential for performance, injury prevention, and overall enjoyment.

If you need to custom dragon boat paddle, welcome to contact us.

Why Master Dragon Boat Paddle Technique?

Understanding why dragon boat paddle technique matters sets the foundation for improvement. Poor form not only reduces efficiency but also increases the risk of injury. According to a 2019 study published in the Journal of Sports Sciences, improper paddling mechanics contribute to over 30% of shoulder and back injuries in dragon boat athletes. Mastering the technique ensures that paddlers use their bodies optimally, distributing load across larger muscle groups rather than relying on smaller, fatigue-prone ones like the arms.

From a performance perspective, an effective technique maximizes propulsion. In a dragon boat, which can weigh up to 2,000 pounds when fully loaded with 20 paddlers, a drummer, and a steersperson, every stroke counts. Data from the IDBF indicates that teams with synchronized, biomechanically sound techniques achieve higher stroke rates—often 60-80 strokes per minute during races—while maintaining power output. This synchronization creates a “run” on the water, where the boat glides smoothly between strokes, reducing drag.

Additionally, why focus on technique? It promotes longevity in the sport. Recreational paddlers who adopt proper form report higher satisfaction and lower dropout rates, as per surveys from the Dragon Boat Canada association, where 75% of participants cited technique training as key to their continued involvement. Technique also fosters team unity; when everyone paddles identically, the boat moves as one unit, enhancing the communal aspect of the sport.

Finally, from a physiological standpoint, good technique engages the core, legs, and back, leading to better cardiovascular benefits. A report from the American College of Sports Medicine highlights that dragon boating, when done correctly, provides a full-body workout comparable to cross-training, burning up to 600 calories per hour.

What Is Dragon Boat Paddle Technique?

Dragon boat paddle technique refers to the coordinated movements used to propel the boat forward using a single-bladed paddle. Unlike symmetrical sports like rowing, dragon boating involves asymmetrical paddling on one side, requiring rotation and balance.

At its core, the technique involves four phases: setup (or recovery), catch, pull (or drive), and exit. The setup positions the body for power generation. The catch is the moment the blade enters the water fully buried at a positive angle. The pull uses body rotation to draw the paddle back, and the exit lifts the blade cleanly to minimize drag.

Key elements include body positioning: paddlers sit with their outside leg forward and inside leg back, locking the knee against the gunwale for stability. The paddle is held with the top hand over the water and the bottom hand guiding the blade. Rotation originates from the hips, not just the shoulders, allowing for a full torso twist.

What distinguishes dragon boat technique is its emphasis on collective power. In a standard 20-paddler boat, as defined by IDBF standards, each stroke must align perfectly. The “A-frame” position—formed by the arms and paddle just before entry—ensures a strong catch. Data from biomechanical analyses, such as those in the International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, show that maintaining a 45-degree blade angle at entry optimizes water purchase, meaning the blade grips the water effectively without slipping.

Technique also incorporates leg drive. With both feet forward or one slightly advanced, the legs provide a stable base, transferring power from the lower body upward. This contrasts with arm-dominant approaches, which lead to quick fatigue.

In essence, dragon boat paddle technique is a blend of strength, timing, and efficiency, designed for high-intensity, short-duration efforts in races typically lasting 2-5 minutes over 200-500 meters.

How to Execute Dragon Boat Paddle Technique: Step-by-Step Breakdown

Mastering dragon boat paddle technique requires practice, but breaking it down into steps makes it accessible. Here’s a detailed how-to guide, focusing on biomechanics and common pitfalls.

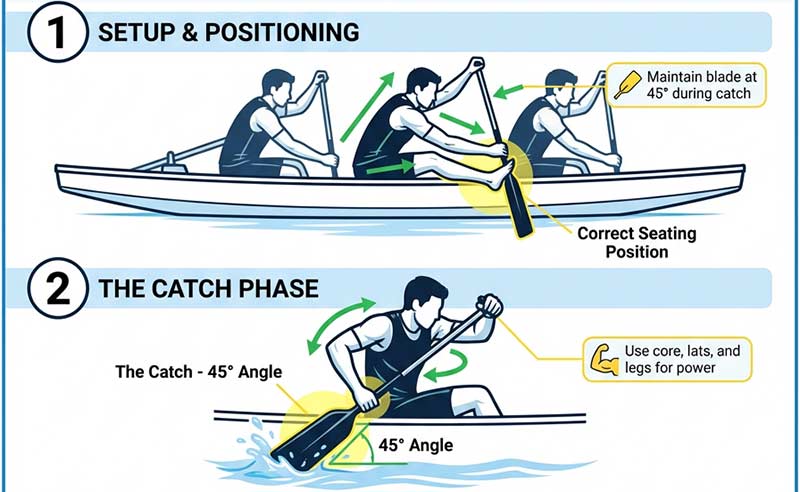

Setup and Positioning

Start with proper seating. Sit on the bench with your outside leg (paddle-side) extended forward, foot braced against the boat’s footrest or floor. Your inside leg bends slightly back, creating a stable base. This positioning allows for hip rotation, which is crucial for power.

Hold the paddle with your top hand (non-paddle-side) gripping the T-handle, arm extended over the water. Your bottom hand (paddle-side) holds the shaft about shoulder-width down. Maintain a relaxed grip to avoid tension.

Lean forward from the hips, twisting your torso so your chest faces inward toward your bench partner, and your back faces the water. This creates the “A-frame”: bottom arm parallel to the gunwale, top arm straight, paddle blade hovering just above the water at a 45-degree angle.

How does this help? It preloads the muscles for an explosive catch, reducing the time the blade spends out of the water.

The Catch Phase

The catch is where power begins. Drive the paddle into the water by pressing down with the top hand while keeping the blade at 45 degrees. Engage your top shoulder and lat muscles to bury the entire blade positively—meaning it’s angled forward to “catch” water without slicing.

Avoid dropping the elbow; instead, squeeze the lat to activate the upper back. This phase should feel like a quick stab, fully submerging the blade before pulling.

How to practice: On land, use a mirror to check your angle. In the boat, focus on patience—don’t rush. IDBF training manuals recommend visualizing “spearing a fish” to emphasize precision.

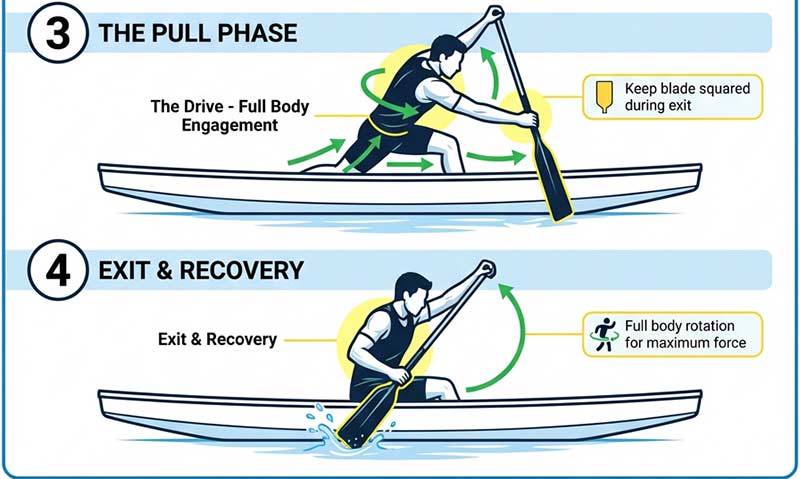

The Pull or Drive Phase

Once caught, derotate your body. Your outside hip moves forward, inside hip back, as your torso unwinds to neutral. Use your core, lats, and legs to pull the paddle back parallel to the boat.

The top hand presses initially to maintain blade positivity, then the body takes over. Legs drive by pushing against the boat, hips rotate, and the core contracts. This full-body engagement sustains load better than arms alone.

How much top hand drive? It’s a press to start, not a full downward push, to keep the blade efficient. Follow through with the body for a smooth pull, ending when the paddle reaches your hip.

Biomechanical data from a 2022 study in Sports Biomechanics journal shows that this rotation increases stroke force by 25% compared to arm-only pulls.

The Exit and Recovery

Exit by lifting the top hand upward, keeping the blade squared against the boat to minimize splash. The bottom hand follows, and the paddle exits cleanly at hip level.

Recover by bringing the paddle forward in a straight line over the water, resetting to the A-frame. Keep the top hand outboard to avoid dipping inward.

How to avoid common errors: Don’t pull past your hip, as it creates drag. Practice slow-motion drills to ensure the blade tucks against the side.

Incorporating Leg Technique

Legs are foundational. Options include both feet forward for solid connection or outside leg slightly advanced for mobility. Both feet forward minimizes loose connections, ensuring power transfers directly from hips.

How it works: Brace legs to rise slightly off the seat during the pull, engaging glutes and quads. This “off-seat” movement amplifies rotation without destabilizing the boat.

Training Tips

Incorporate gym work: Focus on compound movements like deadlifts, squats, and bench presses to build core muscles. Supplement with bodyweight exercises for maintenance.

On-water drills: Practice catch clinics, emphasizing bury and positivity. Time strokes at 60-70 per minute for endurance.

Dragon Boat Paddle vs. Other Water Sports

Comparing dragon boat paddle technique to others highlights its uniqueness.

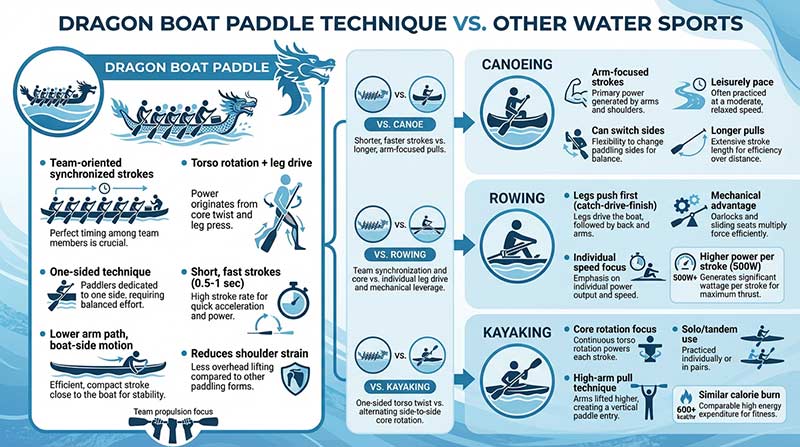

Vs. Canoeing

Canoeing often involves a leisurely, arm-focused stroke with the paddler kneeling or sitting. Dragon boating demands torso rotation and leg drive for power, suitable for team propulsion. Canoeing allows switching sides; dragon boating is one-sided, increasing asymmetry risks but building unilateral strength. Per IDBF vs. canoe federation comparisons, dragon boat strokes are shorter and faster (0.5-1 second) vs. canoeing’s longer pulls.

Vs. Rowing

Rowing uses oars in oarlocks for leverage, with legs pushing first in a “catch-drive-finish” sequence. Dragon boating relies on free paddles, emphasizing upper body rotation over leg extension. Rowing boats are narrower and faster individually, but dragon boats prioritize synchronization. A study in the European Journal of Sport Science notes rowing generates more power per stroke (up to 500 watts) due to mechanical advantage, while dragon boating distributes effort across the team.

Vs. Kayaking

Kayaking uses double-bladed paddles for alternating sides, focusing on core rotation similar to dragon boating. However, kayaks are solo or tandem, lacking team dynamics. Dragon boat technique avoids the high-arm pull of kayaking, opting for a lower, boat-side path to reduce shoulder strain. Data from the British Canoeing association shows kayaking burns similar calories but with less emphasis on explosive starts.

Overall, dragon boat technique stands out for its team-oriented, rotational focus, making it more accessible for groups but demanding precise timing.

Advanced Dimensions: Multi-Faceted Analysis of Dragon Boat Paddle Technique

Biomechanical Perspective

From a biomechanics viewpoint, the technique optimizes force vectors. The 45-degree catch angle creates positive pressure, per fluid dynamics principles, maximizing forward thrust. Rotation reduces spinal load by 20%, as per ergonomic studies in the Journal of Applied Biomechanics.

Physiological Benefits

Engaging large muscles like lats, core, and legs improves endurance. Heart rate data from IDBF-monitored races shows paddlers maintain 80-90% max HR, enhancing aerobic capacity.

Psychological Aspects

Technique mastery builds confidence. Team synchronization fosters a “flow state,” reducing perceived effort, according to sports psychology research in Psychology of Sport and Exercise.

Equipment Considerations

Paddle length (typically 42-50 inches) affects technique; shorter for quick strokes, longer for power. Carbon fiber paddles reduce weight, allowing better form maintenance.

Environmental Factors

In choppy water, technique adapts with shorter strokes. Wind resistance data suggests leaning more forward in headwinds.

FAQ: Common Questions About Dragon Boat Paddle Technique

What if I feel rushed during the stroke?

Focus on patience at the catch. Ensure full blade burial before pulling. Check timing with teammates—rushing often stems from mismatched synchronization.

How do I avoid arm fatigue?

Prioritize body usage: rotate from hips, engage legs and core. Limit arm-dominant strokes; they fatigue after minutes, while body-driven ones sustain longer.

Is one leg forward better than both?

Both work, but both feet forward provides stability via hip connection. Single leg forward allows more mobility but risks loose power transfer.

How often should I practice technique?

Aim for 2-3 sessions weekly, including land drills. IDBF recommends 10-15 minutes of focused technique per practice.

Can the technique prevent injuries?

Yes, proper form reduces strain. Stretch outer lats post-paddle; feel a squeeze during strokes for activation.

What’s the ideal stroke rate?

60-80 per minute for racing, per IDBF guidelines. Start slower for technique focus.

How does technique differ for beginners vs. experts?

Beginners emphasize basics like A-frame; experts refine load feel, achieving “heavy catches” after years.